Re/Marks on "Restoring Truth"

The set of notes concern Indigenous stewardship, eugenics, anti-Asian discrimination, racism, and the importance of publicly interpreting complex legacies.

These notes appear on a wooden sign, in the woods, alongside some dates and the explanatory comment, "Everything on this sign is accurate, but incomplete. The facts are not under construction, but the way we tell the history is."

These are the type of truth-telling notes feared and contested by an administration committed to the Newspeak of "Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History."

From university campuses to our public parks, we're witnessing an administration bluntly wield ascribed cultural authority to constrict how truth and history is understood, valued, and protected. Without minimizing material harms to our neighbors or the erosion of social norms, I must also ask: What will become of the annotated Path to Preservation timeline at Muir Woods National Monument?

This sign and its timeline are the first substantive example I discuss in Re/Marks on Power: How Annotation Inscribes History, Literacy, and Justice. Initiated in 2021, I share this example as inspiration for it demonstrates how participatory and more just social futures can be written by the collective addition of notes to texts. At the time, the effort was described as "in step with a larger racial reckoning," and it was created through "audience-centered interpretation" that "goes beyond a regurgitation of facts and promotes critical thinking."

This literal sign of truth-telling powerfully illustrates how perceptions of the past are always "under construction;" or, in the words of the National Park Service, why a "reflective process is critical to understanding both our history and future." For the NPS, there's a difference between the so-called "restoring" of history and the complexity of historical preservation:

The role of the National Park Service is to preserve history - the good, the bad, the ugly, and everything in between. It’s not our job to judge what history is worth telling, but to share an accurate and comprehensive history.

I fear that the Path to Preservation timeline, and its accompanying set of critical and public annotations, will soon be erased, redacted from a sign that provides park visitors at Muir Woods with more accurate and comprehensive historical context. And why might this happen?

Last Friday, NPR reported that:

The Department of the Interior is requiring the National Park Service (NPS) to post signage at all sites across the country by June 13, asking visitors to offer feedback on any information that they feel portrays American history and landscapes in a negative light.

The New York Times further detailed how the public will be asked to comply in advance, contributing to the censorship of truth:

Staff at the National Park Service, which is part of the Interior Department, were instructed to post QR codes and signs at all 433 national parks, monuments and historic sites by Friday asking visitors to flag anything they think should be changed, from a plaque to a park ranger’s tour to a film at a visitor’s center.

Will a visitor to Muir Woods "flag" the annotated Path to Preservation timeline as something that should be changed? And what of the online NPS article "History Under Construction" that complements the sign? That article leads with the question: "Who chooses how history is told?" In the current political climate, it's difficult to imagine that public-facing resources like the online page will remain published when it observes:

Not all early redwood conservationists supported the eugenics movement, but many of them did. Madison Grant and Theodore Roosevelt are two notable redwood conservationists with ties to the eugenics movement.

And:

When visiting a redwood forest, most are humbled by the towering trees. But to eugenicists, a redwood’s unique resilience to pests, fire, and insects, and its reproductive strength were metaphors for White supremacy.

And:

The process of revisiting timelines is a powerful way to critically ask what is absent from the story and why is it missing. As we examine the answers to these questions, we can start to understand how the stories we tell reflect who we are as a society.

In anticipation of censorship, and as a means to counter-narrate "restoring truth," here's an extended excerpt from Re/Marks on Power about a noteworthy sign at Muir Woods National Monument that "demonstrates how we encounter annotation in everyday environments, and how the marking of signs and symbols can alter our reading of history, memory, and place."

If truth is censored in a forest...

A reminder that Re/Marks on Power is openly accessible for you to read and download; this excerpt appears in "Opening Remarks" (Chapter 1).

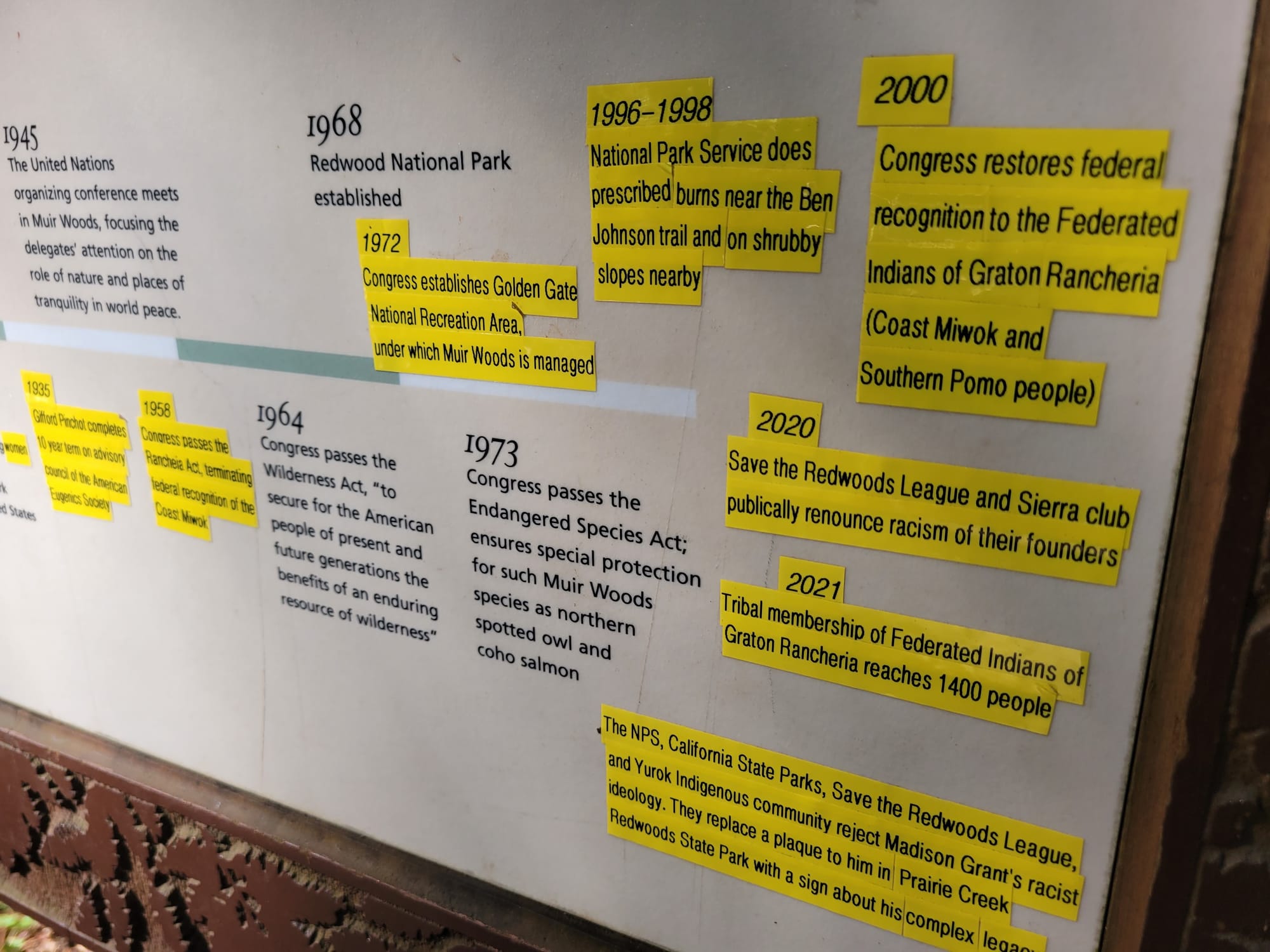

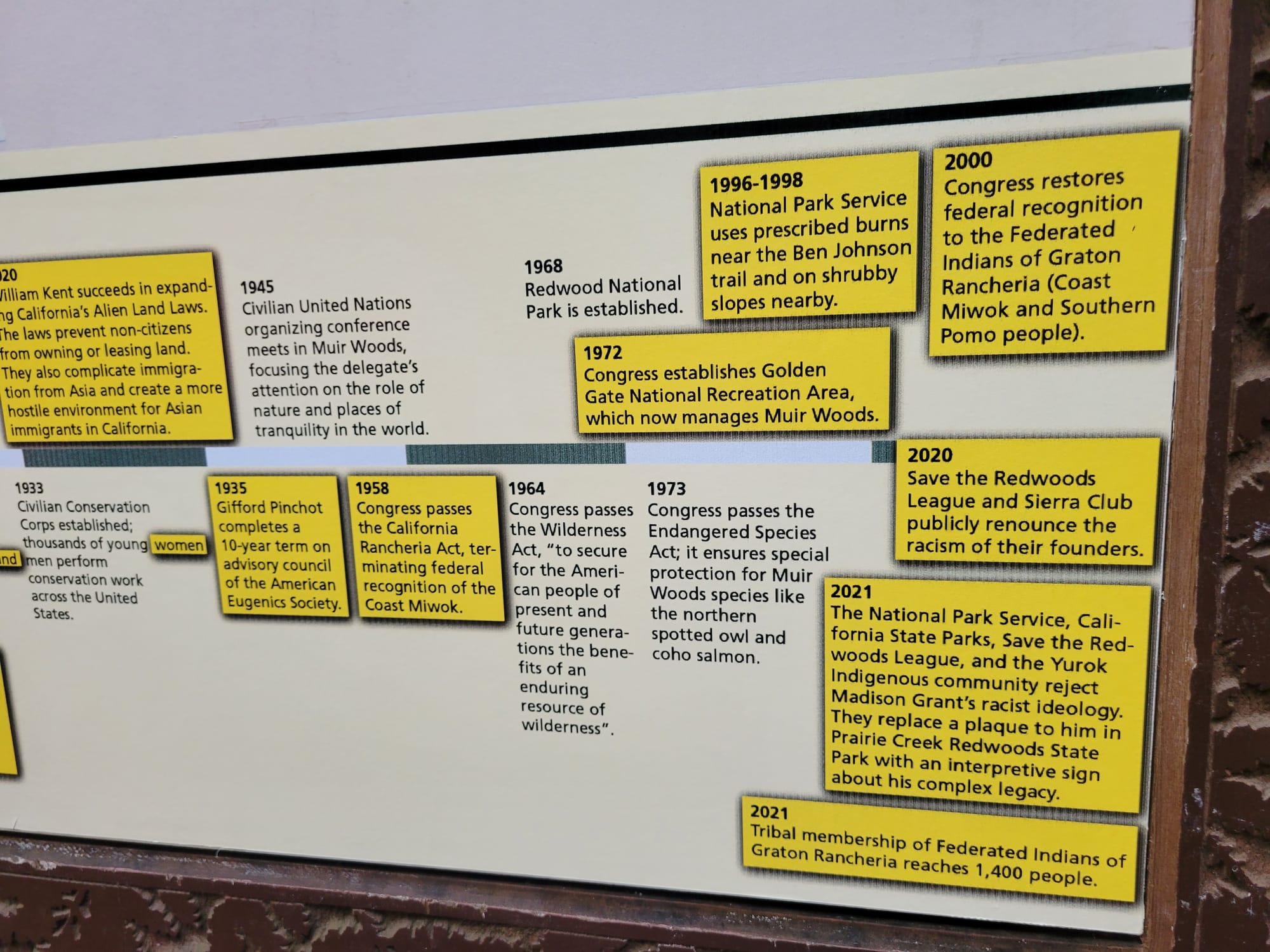

Muir Woods National Monument protects over five hundred acres of land, including an old-growth redwoods forest, and is located less than twenty miles north of San Francisco. Muir Woods staff, in collaboration with an interpretive team at the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, unveiled in 2021 an annotated sign that contextualizes local history and “provide[s] a learning opportunity to park visitors.” This annotation is not neutral and enables public pedagogy. An existing park placard labeled “Saving Muir Woods” was initially bedecked with yellow caution tape and a new laminated sign: “Alert: History Under Construction.” Visitors were invited into social reading, and critical analysis, as they were informed: “Everything on this sign is accurate, but incomplete. The facts are not under construction, but the way we tell the history is.”

This authoritative emendation of Muir Woods’ history is intended to advance a more truthful and complex narrative for park visitors. The effort follows public “truth-telling” about John Muir’s racist commentary, as well as acknowledgment that “other white men involved in the conservation of Muir Woods also have problematic—though lesser-discussed—aspects of their legacies.” The original sign includes a Path to Preservation timeline that was modified with a more comprehensive set of facts presented like yellow sticky notes. Thanks to the practice and visibility of annotation, a sign once perceived as definitive approximated a working draft. Some of the annotated items “originally left out” of Muir Woods’ origin story literally fill in timeline gaps, whereas other additions revise incomplete statements.

A new note labeled “Before European Contact” is the first of the timeline’s nearly two dozen corrections and edits. It states: “20,000 Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo people, living at 850 sites, tend the lands of what is now Marin County and southern Sonoma County. Their prescribed burns care for the forest and their essential needs.” A new 1861 note informs visitors: “Congress removes Indian title to almost all land in California. This action strips Coast Miwok people of title to their ancestral lands, of which Muir Woods is a part.” Another new note, dated 1869, addresses Muir’s racist writing: “John Muir refers to Indigenous people using racist language in his diary, later published, ignoring the genocide they survived. This contributes to an idea that Indigenous people don’t belong in parks.” Edited timeline notes also mention how Gifford Pinchot, first chief of the United States Forest Service, advocated for eugenics (1898), how women of color were excluded from the area’s conservation efforts (1902), and how the politician William Kent—who bought and donated the land that became Muir Woods National Monument—championed anti-Asian policy and rhetoric as with “California’s Alien Land Laws . . . [that] prevent non-citizens from owning or leasing land . . . and create a more hostile environment for Asian immigrants in California” (1920).

One of the many park visitors who read this annotated sign was the educator and scholar Debbie Reese, who is an expert in the representation of Native and Indigenous peoples in children’s literature. In 2019, Reese and I collaborated as part of the Marginal Syllabus project, and we’ve discussed annotation and critical literacy ever since. When I spoke with her about Muir Woods, she recalled the sign as a “wonderful intervention” that changed “my expectation of what someone at a park could do. Somebody there at the park made the decision to do that. Somebody is paying attention. And that is why it is so exciting.” The sign’s annotation is a place-based tether connected to related information that Muir Woods staff also present online, as with commentary about the exclusion of women of color from conservation movements in the early 1900s and Kent’s efforts to prevent Asian immigration. When the sign was first annotated, this land-marking was shared alongside a request for personal reflection because the “History Under Construction” note presented park visitors with two questions: “What do omissions in the historical narrative reveal about our society? How does knowing more shape your perspective on the past and the future?”

I read this annotation as social and justice-oriented activity. This public annotation enables critical historical analysis—and a way to teach truth—that stands in marked contrast to how accurate representations of history have been legislated out of school curricula. Indeed, I write at a moment of entrenched partisan debate in the US about public education and what historical facts and perspectives may be taught in school, how memory and cultural heritage is honored in civic settings, and whose identities and stories are sustained by our institutions. Accordingly, and in Reese’s assessment, Muir Woods’ annotation “was inviting people to revisit, to pause, to rethink, and all of that is a tremendous plus." And today, this landmark now displays the rewritten notes as a more accurate and enduring counternarrative. In 2022, the yellow notes were permanently added as a new feature of the redesigned Path to Preservation timeline. Muir Woods’ annotators rewrote provenance and place, and authored an opportunity for the public to connect the historical record with accessible entry points for discussions of truth and justice. Throughout Re/Marks on Power, we will read how the sociality and vitality of annotation shapes new narratives of public memory and belonging across learning environments.

Re/Marks at MYFest

Back in 2022, I helped my dear colleagues Maha Bali and Mia Zamora organize the first "Mid-Year Festival," or MYFest, a months-long online professional learning experience celebrating critical pedagogy and open education. Now in its fourth year, MYFest is rooted in a commitment to intentionally equitable hospitality, or "a praxis that means our organizers and facilitators take seriously their responsibility to intentionally create spaces that feel welcoming to everyone, especially those farthest from justice."

Tomorrow, on Wednesday the 18th, I'll be facilitating a session titled "Re/Marks About Annotation, Learning, and Power." If you’re an annotation-curious educator, librarian, scholar, or avid reader, join us to critically question how annotation has and can be composed as you mark both your books and public discourses.

Learn more about MYFest, a "three-month celebration of community, care, and co-created learning," and note that registration is pay what you can.

Purchase: Order Re/Marks on Power via PRH and use code READMIT20 to receive 20% off your purchase of the book.

Share: Thanks for sharing Re/Marks on Power, here's a special shoutout to Jason on LI for writing about the power of annotation, as well as Duke Today for featuring my book!

Review: Your reviews on sites like Amazon and Goodreads are valuable and help introduce new readers to the book, so please add your thoughts.

Know an annotator who should be featured in Reading Re/Marks? Send me a note!

Member discussion